Survival is one of the common themes between Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar and Ridley Scott’s The Martian. For the former, the stakes are no less than the human race’s continued existence. In the latter, one man is used as a metaphor to show what the human race can achieve when they unite to accomplish a common goal. However, both films eventually have the same outcome: Due to their attachments to one another, humans push themselves beyond the knowledge and abilities they thought they once possessed. Both show that science applied with cold logic will always be surpassed by that same science used the motivation of attachment, or love. As a result, humans save themselves and become their own alien messiah in these films while also eschewing a number of other potential false saviors along the way and aided by moments of overt religious imagery. Finally, both films also remind us about the need to continue exploration, and both offer their own versions of cautionary tales about what happens if we do not.

In Interstellar, the world is slowly dying. NASA, working in secret, kicks off a three-pronged plan. First, Dr. Hugh Mann (Matt Damon) will lead 12 scientists as scouts through an intergalactic wormhole placed by some unknown entity called “them” to another galaxy to find a new home for the species. Meanwhile, at home, Dr. John Brand (Michael Caine) will solve the problem of moving the entire human race to that planet, once found. The plan’s third prong is the film’s focus and that’s where the story picks up: Roughly a decade after Mann has left. Brand continues to struggle with his equation, but time is running short. He enlists the crew of the spaceship Endurance, including Amelia (Anne Hathaway) and Cooper (Matthew McConaughey), to fly through the wormhole, collect the data from the scouts, and return. As a safeguard, the Endurance carries thousands of fertilized eggs to start a new human colony if things go wrong.

When the Endurance arrives at Mann’s planet and wakes him up, the terrible truth emerges: Brand’s equation was solved decades ago, and there’s no hope for the humans that remain on Earth. This includes Cooper’s children, Murphy and Tom, whom he left behind while trying to save them, and the other humans left on the planet. Mann and Brand lied to NASA and everyone else because they thought it was the only way to convince people to save the species when they could not save themselves. When asked why Brand lied, Mann coldly says:

“Because he knew how hard it would be to get people to work together to save the species instead of themselves or their children… Evolution has yet to transcend that simple barrier. We can care deeply, selflessly about people we know, but that empathy rarely extends beyond our line of sight.” (“Interstellar”, 1:43:33).

This cold application of science and logic without attachment is the closest thing to a true villain in Interstellar, other than the dying Earth itself. It’s ironic that Matt Damon’s character delivers it as, less than a year later, he would return to the silver screen as Mark Watney in The Martian, a character who is saved due to the collected efforts of mankind. When Mark is accidentally left behind on Mars, the world eventually comes together to contribute towards saving him. It takes the joint efforts of NASA, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the Chinese space agency, and the other Martian explorers led by Commander Lewis (Jessica Chastain) to bring Mark home from the red planet. In the film’s final moments, crowds gather across the world and cheer for Mark’s eventual salvation.

However, Mann’s quote does ring true, even in the more utopic world of The Martian, where no one really questions whether or not they should pursue saving Mark. But there are various points of view at work. For example, Teddy Sanders (Jeff Daniels), the Director of NASA, applies more cold logic than anyone else in the film. “The closest thing to an antagonist the film conjures is NASA administrator Teddy, but even he is just trying to do what is best for NASA’s public image” (Weigel). Teddy’s primarily concerned with public relations and NASA’s budget, and though he would like to save Mark, salvation isn’t necessarily at the top of his list of priorities. That’s why, when presented with a risky plan to save Mark using Lewis and her crew, Teddy balks. As it’s said succinctly in the film, “We either have a high chance of killing one person or a low chance of killing six people. How do we make that decision?” (“The Martian” 1:26:00). Teddy, knowing that Lewis’ crew has an attachment to Mark and will have no qualms about putting their lives on the line for him, chooses otherwise. In a sense, Teddy is playing god, choosing to risk Mark’s life rather than allowing Lewis and her crew to make the decision themselves.

We can understand Teddy’s motivation, even if we don’t agree with it. He’s not necessarily marooning Mark, after all, but just not prioritizing him. If he’s playing god, it makes him a false one, and thus mirrors the decisions of Mann in Interstellar. Mann, who has no attachments of his own, is dismissive of Cooper’s attachments to his children and thinks they make him weak. “During the voyage, (Amelia) describes Dr. Mann to Cooper as the most ethical and intelligent human being. But when the Endurance finally arrives at the planet where Mann has landed, his impurity soon comes into view.” (McGowan). McGowan’s choice of impurity in a Biblical sense is an interesting one, as Mann views himself as humanity’s messiah. “Even though he propelled himself into the void of space with only a small chance of surviving, he tells Cooper when they are alone, ‘I never really considered the possibility that my planet wasn’t the one.’” (McGowan). Mann, who was supposedly “the best of us” (“Interstellar” 51:43) believes this about himself. It never occurred to him that he wouldn’t be the “man” to save humanity. Mann and Teddy are both false messiahs because their aims, while scientific, do not include a measure of human attachment.

However, if Mann and Teddy are both false messiahs, then who are the true ones in these films? While Interstellar establishes an alien “other” at the beginning of the film, the supposed “they” who placed the wormhole that allows Mann, Cooper, and everyone to escape the solar system to begin with, there is no immediate alien presence in The Martian (unless you count Watney, Lewis, and co. exploring the surface of Mars in the film’s opening scenes). However, the film’s title itself, The Martian, is actually unironic. At the 28:40 mark of the film, Mark has grown his first potato plant in an effort to save himself. As Mark later explains with a bit of a grin to his NASA video log, “They say that once you grow crops somewhere, you’ve officially colonized it. So, technically, I colonized Mars. In your face, Neil Armstrong” (“The Martian” 1:00:35). At this point, Mark has become “The Martian,” and all other humans have become his “alien other.” When Lewis returns with her crew at the end of the film, she assumes the role of Mark’s alien messiah.

Consider Mark’s constant use of video blogs throughout the film. As a narrative device in film, they’re absolutely necessary, as two hours of watching Matt Damon wander around the NASA hab and the planet wouldn’t be terribly compelling. But as a character, Mark uses them to assuage the loneliness of spending a year and a half as (presumably) the only sentient life form on the planet. He talks to them constantly, sharing every detail of his life, his hopes, his successes and so on. “Observes (Matt) Damon, “(Mark’s) not a guy by himself on an island—it’s a guy by himself on a planet who has the expectation that he’s being observed. There are Go-Pros and cameras all around… He’s behaving with every intention that these things will be discovered” (Carroll 131). But the film makes it clear that it’s unlikely that another mission will ever visit Mark’s location (“The Martian” 31:00), though Mark doesn’t know this. As “The Martian,” Mark knows that the only people who might ever see the video are visitors from NASA, who he hopes will also be his saviors. That makes these videos much like prayer – messages that may or may not be answered by a potential messiah.

Interstellar uses the same video device, with an interesting reversal when considering the two films side by side. In The Martian, it’s Matt Damon’s character waiting to be saved by someone at NASA, who ultimately turns out to be Lewis’ Jessica Chastain. In Interstellar, the messages are sent by Cooper’s adult children, Tom and Murphy, and Murphy is played by none other than Chastain. Bitter over Cooper’s departure, Murphy steadfastly refuses to communicate with Cooper, choosing to believe in the falseness of Dr. Brand and, by extension, Matt Damon’s Dr. Mann, taking on their beliefs as her own. She only uses the videos to express her anger and doesn’t actually believe Cooper is there listening to her. As such, when she discovers Brand’s lie, this hits her on multiple levels: As a scientist and human.

“(Brand) believes that he alone is capable of thinking beyond his own individuality and as a species. In a conversation with Murph just before the professor’s death, Professor Brand’s laments humanity’s inability to think like he can, and yet his supposed exceptionality is what makes him a reprehensible figure.” (McGowan).

Like Mann and Teddy, Brand is a false god. He assumes his exceptionalism and supposed objectivity qualifies him to be the ultimate arbiter of the fate of the human race. Mann admits as much, saying Brand “was prepared to destroy his own humanity in order to save the species. He made an incredible sacrifice.” Cooper refutes this, “An incredible sacrifice is being made by people on Earth who are going to die. Because in his arrogance he declared their case hopeless.” (“Interstellar” 1:43:40). With Brand gone, Murphy is adrift, and so she returns to the only attachment she has left: She tries to save her brother Tom and his family.

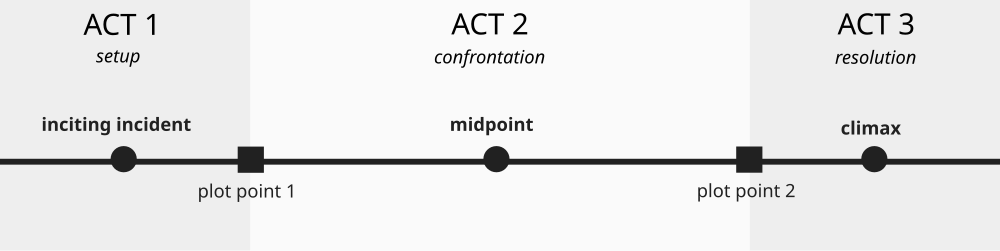

Unlike Murphy, Tom continued to send messages to his father throughout the decades and speaks to Cooper more like Mark Watney speaks to his unknown audience: Like someone would speak to a dead relative’s grave or might pray to God. Tom speaks into the camera without knowing if anyone is listening, but he hopes. His father has promised him and his sister that he will return with salvation. So, Tom persisted. But after a series of personal setbacks, Tom becomes embittered. His son and his grandfather have died. “You aren’t listening to this, I know that,” Tom says. “All these messages are just drifting out there in the darkness… I guess I’m letting you go.” (“Interstellar” 1:21:18). At this moment, both children have now lost faith in their father as a potential messiah. However, this is also the precise moment when human attachment – the true “alien messiah” in Interstellar – reveals itself for what it truly is. Back at the film’s beginning, we witnessed two moments which, for lack of a better term, are deemed “supernatural” and had yet to be explained. First, there’s the “ghost” in Murphy’s bookcase. The bookshelf sends messages to Murphy and Cooper through seemingly supernatural forces of gravity, among them the coordinates to NASA, which is our film’s true inciting incident. The second is the existence of a wormhole to a galaxy with habitable planets. Without both of these things, there is no story.

Taking one last “Hail Mary” attempt at saving his children in the climax, Cooper flings himself and his robot assistant TARS through the wormhole. He hopes to collect the missing data for Murphy to complete Brand’s formula to save humanity and also to get home somehow. Things don’t go as planned, and Cooper has to eject while in the wormhole. He gets sucked into a four-dimensional tesseract, which turns out to be every moment of time behind Murphy’s bookshelves. At this moment, Cooper understands these supernatural phenomena and who is “behind” them. As Cooper says, “They didn’t bring us here at all. We brought ourselves.” (“Interstellar” 2:28:43). Cooper, now understanding that the saved human beings have “returned” to help themselves, remembers the coded messages in the bedroom, and sets about his plan of communicating the missing data to Murphy. Inspired by her dormant connection with her father, Murphy has revisited her childhood bedroom and discovers the message. At this point, she becomes aware that her father is the savior for whom she’s waited so long, even if she can’t exactly conceive how. She knows it’s her father, and Cooper understands that he was put in the position to save Murphy by humans who had evolved over the course of hundreds if not thousands of years, who used Cooper and Murphy’s connection to save humanity.

This is where the comparison of the films takes another ironic turn. In Interstellar, Chastain’s Murphy uses the secret message to save humanity as a whole. In The Martian, Chastain’s Lewis is also delivered an encoded message. This one’s from NASA’s Flight Director Mitch Henderson (Sean Bean), who fundamentally disagrees with Teddy’s playing god. In the message, he delivers the flight maneuvers and math that would be required for her and her crew to return to Mars to save Mark. Predictably, due to her and her crew’s connection with Mark, Lewis rallies the crew and returns, setting herself up as the messiah who will pluck Mark from the suffering he’s endured on the planet and take him off into the heavens.

Mark’s removal from the planet via the NASA spacecraft is one of several religious images in the film. Perhaps the most overt comes in the first act when Mark desperately needs something that burns to create water to help his potato plants grow. As Mark says, “NASA hates fire… So, everything they sent us up here with is flame-retardant with the notable exception of Martinez’s personal items” (“The Martian” 25:42). Mark holds up an actual crucifix to the camera, which is made of wood. Carving it, Mark eventually uses the crucifix to light a fire and create water, turning him into a colonist and, ultimately, “The Martian.” The sequence is full of religious imagery, as Mark not only uses an image of a messiah to save himself but also to “create” water and eventually grow planets on what was formerly a dead planet.

“(Mark) looks at the figure of Christ on it and says that he thinks that Jesus wouldn’t mind him using it to save his life. Though this never develops beyond a joke, it is interesting to see how it ultimately is a kind of salvation through the cross–this time in a very literal sense” (Wartick).

Interstellar has its own version of deliverance, akin to Moses’ exodus from Egypt or Noah’s Ark. “The movie ends with a futuristic version of Noah’s ark… finally saving humanity.” (Nir 62). Of all of the religious symbolism seen throughout Interstellar, this is the most overt. It also leads us into the film’s climax where due to relativity, roughly 80 years have passed between Murphy and Cooper’s visits, but their connection is evident when they finally see each other again. Having fulfilled his promise to Murphy to return, Cooper is now unmoored. His purpose is complete. But Murphy has one last mission for him: Return to Amelia, who, as the last surviving member of the Endurance, has gone off to set up a new colony on Edmunds’ planet. It’s also revealed that Edmunds is dead, and Amelia, who presumably knows nothing of the ark, considers herself the last living human being in the known universe… not all that different from Mark Watney.

Here, Cooper and Murphy acknowledge that, since love saved them, Amelia will need love to survive. So, despite having precious few moments with Murphy, whom he tried for eight decades to return to, Cooper leaves. We can accept this because we know “the love between father and daughter has changed into more selfless love that can be generalized for all mankind.” (Xinyi 211).

The message of Interstellar is clear: The world is in trouble. Overpopulation. War. Excess. At our core, human beings are explorers, and we no longer explore. As Cooper laments in the film’s beginning, “We used to look up at the sky and wonder at our place in the stars. Now we just look down and worry about our place in the dirt.” (“Interstellar” 16:45). In the film, exploration has gone by the wayside as troubles at home have mounted, as administrators couldn’t justify a budget for NASA while others are starving.

Nolan didn’t make this up. There’s a lot of support for eliminating NASA even now. The Congressional Budget Office has a plan available to the public for essentially eliminating all manned space exploration in the United States as part of a budget reduction mechanism (CBO.gov). Just last March, the real-life version of Teddy Sanders, NASA’s Administrator Bill Nelson, went before Congress to warn of the “potentially unrecoverable impacts upon the objectives that the President and Congress have set for NASA” (Foust).

In a final ironic twist between these two films, Professor Bryant Sculos wrote a scathing review of The Martian for Class, Race and Corporate Power, in which he lamented the use of resources to save Watney and suggested that NASA only exists to further the excess spending of the military-industrial complex, rather than seeing a need to explore.

“Mark Watney seems like a great guy, but why doesn’t he ever suggest that maybe, just maybe, coming to save him isn’t the best use of even NASA’s resources, never mind the planet’s he was originally a resident of? Probably for the same reason most people don’t question NASA’s $18 billion budget now. Ignorance. Manipulation. Self-interest. In order for democracy to work, and to work for the people, it must be conditioned towards rational… not goals that are provided by Boeing and Lockheed-Martin” (Sculos).

Sculos sounds like a real-world Dr. Mann, someone whose empathy does not extend beyond his line of sight. Presumably, if Mark were Sculos’ brother, he’d be all about the big spend to save him. Apparently, it has cost nearly a trillion fictional dollars to save Matt Damon’s characters from far-off places in his career, including $700 billion in these two films alone (Time).

Like all good science fiction, Interstellar and The Martian exist to reflect real-world realities: That human beings, when they get into trouble, must unite and find a way to save themselves. To be their own messiah. As the planet becomes increasingly overpopulated and resources dwindle, exploration becomes increasingly necessary, not redundant, as Sculos and others like him might see it. Humans have explored throughout their entire existence for this very reason and both of these films remind us that there’s a great, big universe of possibilities out there. If we can’t see beyond our line of sight to doing it to save the species, then we need to think smaller and closer to home and use our attachments to guide us beyond what we think is possible to save ourselves. Our grandchildren will thank us for it.

Originally published as part of the Master’s in Film and Media Studies program at Arizona State University.

WORKS CITED

Carroll, Siobhan. “Lost in Space: Surviving Globalization in Gravity and the Martian.” Science Fiction Studies, vol. 46, no. 1, 2019, pp. 127–142, https://doi.org/10.1353/sfs.2019.0024. Accessed 30 Nov. 2023.

CBO.gov “Eliminate Human Space Exploration Programs | Congressional Budget Office.” Cbo.gov, 13 Dec. 2018, www.cbo.gov/budget-options/2018/54771.

Foust, Jeff. “NASA Warns of “Devastating” Impacts of Potential Budget Cuts.” SpaceNews, 24 Mar. 2023, spacenews.com/nasa-warns-of-devastating-impacts-of-potential-budget-cuts/.

Interstellar. Directed by Christopher Nolan, Warner Brothers, 26 Oct. 2014.

The Martian. Directed by Ridley Scott, Twentieth Century Studios, 24 Sept. 2015.

McGowan, Todd. “Anti-Gravity: Interstellar and the Fictional Betrayal of Place.” Jump Cut: Review of Contemporary Media, vol. No. 57, no. Fall 2016, 2016.

Mizan, Zulkhairi, et al. “An Analysis of the Theme in the Film of Interstellar.” Research in English and Education Journal, vol. 8, no. 3, Aug. 2023, pp. 150–159, jim.usk.ac.id/READ/article/view/27603. Accessed 26 Oct. 2023.

Nir, Bina: Biblical Narratives in INTERSTELLAR (Christopher Nolan, US/GB 2014). In: Journal for Religion, Film and Media, Jg. 6 (2020), Nr. 1, S. 53-69. DOI: 10.25364/05.06:2020.1.4.

Sculos, Bryant W. “The Martian: A NASA-Tionalist Utopia.” Class Race Corporate Power, vol. 3, no. 2, 13 Nov. 2015, https://doi.org/10.25148/crcp.3.2.16092103. Accessed 30 Nov. 2023.

Time. “Rescuing Matt Damon’s Characters Has Cost More than $900 Billion.” Time, 28 Dec. 2015, time.com/4162254/cost-of-rescuing-matt-damon/#:~:text=Based%20on%20estimated%20fictional%20costs. Accessed 30 Nov. 2023.

Wartick, J. W. ““The Martian” – Hope, Humanity, and God- a Christian Look at the Film.” J.W. Wartick – Reconstructing Faith, 12 Oct. 2015, jwwartick.com/2015/10/12/martian-movie/. Accessed 30 Nov. 2023.

Weigel, Brandon. “Review #5: The Martian.” Sci-Fi Movie Reviews, 8 May 2018, medium.com/sci-fi-movie-reviews/review-5-the-martian-734726ce7660. Accessed 30 Nov. 2023.

Xinyi, Ma, and Hua Jing. “Humanity in Science Fiction Movies: A Comparative Analysis of Wandering Earth, the Martian and Interstellar.” International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Translation, vol. 4, no. 1, 30 Jan. 2021, pp. 210–214, https://doi.org/10.32996/ijllt.2021.4.1.20. Accessed 26 Oct 2023